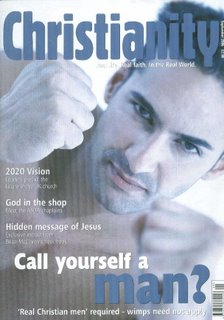

The September edition of Christianity magazine carries a letter of mine which really sums up my perspective on Christianity. I wrote the letter in response to the editorial written by the editor John Buckeridge in the July edition of the magazine. Here is my letter:

The September edition of Christianity magazine carries a letter of mine which really sums up my perspective on Christianity. I wrote the letter in response to the editorial written by the editor John Buckeridge in the July edition of the magazine. Here is my letter:

***

In response to the editorial in the July ‘Christianity’ let me say that I support John Buckeridge’s policy of including a mix of articles that are less than good news and/or touch on controversy. For example, if the policy of ‘Christianity’ is to tell it as is, then the sharp disagreements existing between many Christains should be represented. After all, the Bible itself is frank about controversy amongst believers (Gal. 2:11, Acts 15:39). Christians are the beneficiaries of one universal message of salvation, but the various Christian subcultures hosting that message may split acrimoniously over such things as tithing, the history of creation, church structures, blessings, and healing etc, as recent correspondence in ‘Christianity’ suggests. We must be honest about the real state of affairs in Christendom.But there is good reason for this state of affairs. The Christian view is that salvation is not attained through visible membership of a single highly integrated religious group. Many religious cults see it that way but true Christianity is different, being first and foremost a personal response demanded by the message of redemption. A faith such as Christianity, which majors on message rather than membership, is not easily confined to one tight knit group of people because, like any freely diffusing message, it can cross partisan barriers and take root where it wills. In Christianity where message is primary and membership secondary, there is a consequent trade off between freedom and disharmony. We may, of course, find disharmony unacceptable and do all we can to bring accord, but it is a fact that ‘The Church Invisible’ is distributed over a wide cross section of sometimes squabbling Christian subcultures. The quasi-Christian cults shortcut this problem, of course, with a very strict selection and management of their member’s beliefs, and when tricky questions are asked this is taken as evidence of unbelief. In contrast, real Christianity is no toy town cult, but has all the rough edges of a work in progress.

In line with ‘Christianity’s’ policy of handling difficult material I was gratified to read Adrian Plass’ article on healing (May). This article challenged the conspiracy of silent pretense and religious spin sometimes surrounding the subject of healing and which is reminiscent of the emperor’s new clothes.

However, it seems that John Buckeridge was criticised for editing a magazine that occasionally breaks the silences over awkward questions. This criticism used some spiritually intimidating language, which included accusations of unbelief and a call to repentance. Not only does this kind of criticism show just how partisan evangelicalism can get, but it also indicates that the temptation to arrive at a contrived harmony using the methods of the cults – namely, through silence, pretense and spiritual bullying – is never far away. If Christianity went down that road it really would be in trouble.

You may be able to quarantine a membership, but you can’t quarantine a message.